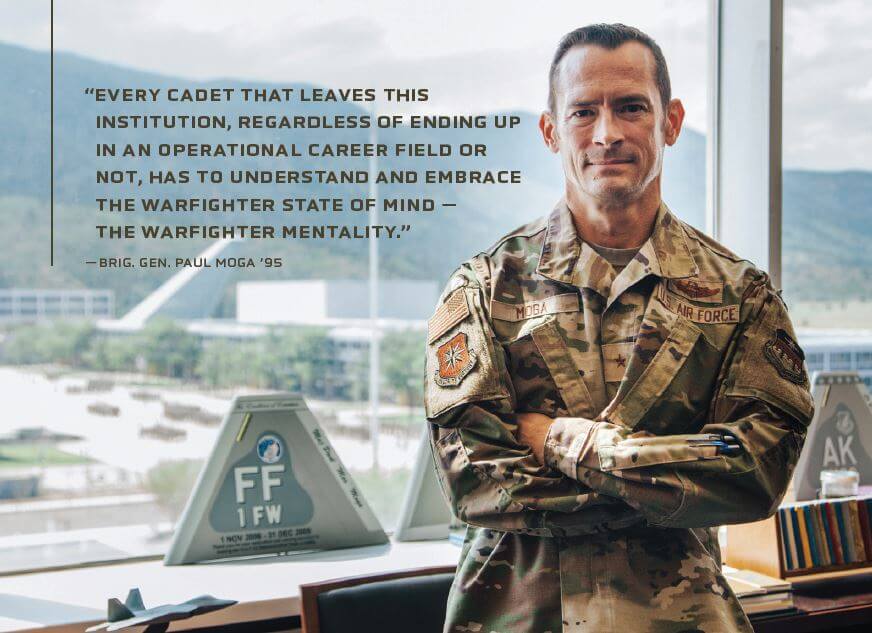

Return to Jacks: New commandant strives to instill warfighter mentality among cadets

By Jeff Holmquist, Association of Graduates

By the end of his run through the assault course, Brig. Gen. Paul Moga ’95 is dripping in sweat, caked in mud and smiling from ear to ear.

As a basic cadet in 1991, Moga successfully navigated the various physical and mental challenges in Jacks Valley, but he never thought he’d be back here — 30 years later and serving as commandant of cadets at his alma mater.

In the early days of his new role, Moga was asked if he would like to relive some of his basic cadet glory days. He admits he didn’t give it much thought before agreeing.

“Originally, I thought I was just going to show up, see and observe,” he laughs. “Then both OICs asked me if I wanted to run the courses. I don’t know what prompted me to say yes. Probably a lack of judgment.”

Over two days, Moga actually ran both the obstacle and assault courses alongside cadets. He loved the challenge but was pretty exhausted by the end.

“Let’s just say my 48-year-old body was not happy with my 18-year-old brain,” he says. “If it were not for the fact that I had a flight of basics on the obstacle course that were looking out for me, and two upperclassmen who ran the assault course with me that were my wingmen to get me through, I don’t know if I would have made it.”

Ultimately, the Jacks Valley experience proved to be a key lesson in leadership for the Cadet Wing. Moga ably demonstrated that officers should be in the trenches alongside their subordinates.

“I learned pretty early on in my career that you have to do as many things as you can in your organization that your people do,” he explains, “and not just the fun and the easy ones, but the difficult and hard ones. I had to at least show up and try.”

In addition, he delivered a powerful message that the new commandant is ready and willing to do what it takes to build and inspire the next generation of warfighters.

Early Influences

Moga’s father, an Army dentist, died when the future commandant was just 2 years old. He doesn’t have any memory of his dad.

As a consequence, Moga was raised by a strong, single mother — a schoolteacher who emphasized the importance of education to her four children.

“I don’t know what my mom put in the water, but she found a way to get four delinquent kids to pretty good places in life,” he says. “I’m super proud of my mom. I don’t know how she did it.”

Moga attended a private, Catholic military school in Minnesota as a teen. He was part of its Junior ROTC program for four years, even though he wasn’t certain he’d ultimately join the military.

An older brother attended West Point, returning home on holiday breaks to re-count the horror stories of Plebe life. By the time he was a high school senior, Moga decided he wouldn’t follow in his brother’s footsteps, but he would instead pursue an appointment to USAFA.

“There was no way I was going to West Point as a freshman with my brother as a junior,” he admits. “That would have been a big mistake. Because of my brother, I got pushed toward the Air Force … and I thank him for that.”

Unexpected Path

A biology major while at the Academy, Moga had no specific career goals in mind through most of his cadet years. Not pilot-qualified when he arrived, Moga eventually received a waiver that allowed him to become a pilot.

While at Soesterberg Air Base in the Netherlands for an Ops Air Force visit, Cadet Moga enjoyed a backseat ride in an F-15B.

“I puked seven times,” he laughs, “but I was like … I think I want to do this in the Air Force.”

After graduation and a year in USAFA’s Biology Department, Moga attended pi-lot training at Laughlin Air Force Base in Texas. He would become an F-15C pilot, with his first operational tour in Alaska. He later served as an instructor.

His next assignment was Tyndall Air Force Base in Florida, where he would transition from the F-15 to the F-22. He was a member of the initial cadre to stand up the F-22 schoolhouse in 2004-05.

From there, he headed to Langley Air Force Base in Virginia to help stand up the F-22 demonstration team.

“That was a phenomenal and interesting experience that I never thought I was going to be asked to do in the Air Force,” he says. “I’m just glad I survived and didn’t break anything.”

After a short stint on the Air Combat Command staff, Moga was assigned to Elmendorf Air Force Base in Alaska as an F-22 director of operations and squadron commander. Schooling at the NATO Defense College followed, and then a staff tour in Stuttgart, Germany, on the United States European Command (EUCOM) staff.

In 2015, Moga became vice wing commander at the 80th Flying Training Wing at Sheppard Air Force Base in Texas.

“It was a phenomenal job,” he reports. “I got to see a lot of Academy graduates who showed up as lieutenants to go through the pipeline course at Sheppard. It was a fantastic opportunity.”

Two years later, Moga was commander of the 33rd Fighter Wing at Eglin Air Force Base in Florida, flying the F-35.

After another staff job in the Pentagon, Moga had a brief stint at Peterson Air Force Base in Colorado.

Then, unexpectedly, he was told on a Friday that he had an interview with then USAFA Superintendent Lt. Gen. Jay Silveria ’85 on Sunday concerning the commandant of cadets role.

Following interviews with Gen. Silveria, the secretary of the Air Force, the chief of staff of the Air Force and the chief of Space Operations, Moga landed the job. He was shocked.

“It took a while for it to sink in,” he says. “Never, when I was a cadet here or throughout my career, did I even think I’d be back here as the commandant. My KTP [Keep the Pride] ’95 classmates likely didn’t either.”

His wife, Amanda (Jones-Greco) ’01, was equally as speechless at the new assignment.

“But the more and more we both thought about it, the more excited we were by the opportunity,” he reports. “She is just as thrilled as I am to be back here at our alma mater.”

Let’s Rock

You can see it in his eyes — Moga is laser-focused as he begins his new role at USAFA.

“It’s an extraordinary opportunity that I don’t take lightly,” he says. “Not a lot of people get this chance to make a difference and shape a generation’s worth of leaders for the Air Force and the Space Force.”

Moga admits the job won’t be easy, but his background and unique skill set have prepared him well for this particular job.

“I’m really excited to pay it back and pay it forward,” he says. “I think I have an obligation to do both, based on what the Academy has done for me personally and professionally. One of the best ways I can pay this institution back is by paying it forward into the next generation.”

Key to his success on the job is the sup-port he receives at home, Moga says. His wife, a former F-15 and F-22 maintainer while in the Air Force, and their two children — Madeline, 12, and P.J., 10 — are behind him 100%.

“Thankfully, I’ve found a way to convince them to continue this journey with me,” he adds. “I wouldn’t do it without them.”

Top Priorities

In the early days of his tenure as commandant, Moga is assessing the state of the Cadet Wing and developing an effective game plan for the future.

His short-term priority is bringing the Academy back to some sense of normalcy, despite the lingering global pandemic.

“We need to smartly separate ourselves from the fight we’ve been anchored in over the last year and a half, and put it in the 6 o’clock and extend away,” he says.

Not to forget the lessons learned, he adds, but to start moving forward again.

“I need to do that quickly,” he suggests. “I’m not willing to delay. I’m completely comfortable with taking calculated risks to get us back to where we were before and then get us to somewhere better. That’s where I think the cadets are very hungry and motivated to get to.”

His longer-term priority is instilling the future warfighter mentality across the Cadet Wing.

“Every cadet that leaves this institution, regardless of ending up in an operational career field or not, has to understand and embrace the warfighter state of mind — the warfighter mentality,” he says. “Whether they end up in combat or supporting those who do, that mentality will serve them well throughout their careers and throughout their lives.”

Militarily, that emphasis is necessary because the cadets will be entering an era of strategic competition that will require innovative problem solving, future-focused planning, critical thinking, risk taking and a warrior ethos, he says. The commandant’s team will work in partnership with the Center for Character and Leadership Development (CCLD) and the Dean of the Faculty to hone that mindset.

With the launch of the Institute for Future Conflict, Moga says the Academy is on the right track to ready cadets for the future — no matter what it may look like.

The road forward can seem over-whelming, Moga says, but there’s no choice except to continue to fully equip these future officers to meet the challenge.

“There’s no playbook to this,” he admits. “We’ve got to figure out how to get this as right as we can, to set these phenomenal young Americans up for success.”

Heritage Revisited

As he works to achieve his mission of developing forward-thinking leaders of character, Moga says he applauds some of the training changes within the Cadet Wing that have occurred in recent years.

“The Cadet Wing has, for all the right reasons, evolved over the last 25 years since I left with regards to how we train, what we train to, and why we train to it,” he explains. “There were a lot of things that were happening inside this Cadet Wing that were being done under the auspices of tradition and heritage. But they really had no place in this institution, and I’m primarily referring to hazing, maltreatment and bad behaviors. I think we have done a good job of getting away from those, because they were not outcomes-based.”

Other previous changes didn’t come about because of poor training techniques or bad behavior.

“I’m considering bringing some of those back,” he says.

Case in point — Form O-96. Moga has already reinstated the “fast, neat, average…” survey at Mitchell Hall to introduce cadets to that important piece of USAFA history.

He’s evaluating other former practices and efforts that could be reinstated in the future in an effort to focus on discipline, decorum, duty, traditions and institutional pride.

Forward March

Moga says he’s been impressed with the capability and eagerness of today’s Cadet Wing.

“What an amazing group of young Americans,” he says. “They are better than I ever was when I was here as a cadet. They’re smarter, they’re harder working, they’re more forward thinking, they’re more pioneering, they think more critically, they’re hungrier.”

Most importantly, the cadets are wanting to put the pandemic in the rearview mirror and move on.

“Knock on wood, the worst is behind us,” he says of the pandemic.

Some of the lessons learned over the past two years will remain part of the institution’s regular routine, he notes.

“There were certain things that, out of necessity, we were forced to do that are actually worthy for consideration to continue doing,” he says. “They made us more efficient or more effective.”