Building diversity: Transgender couple speaks at NCLS about military service, life

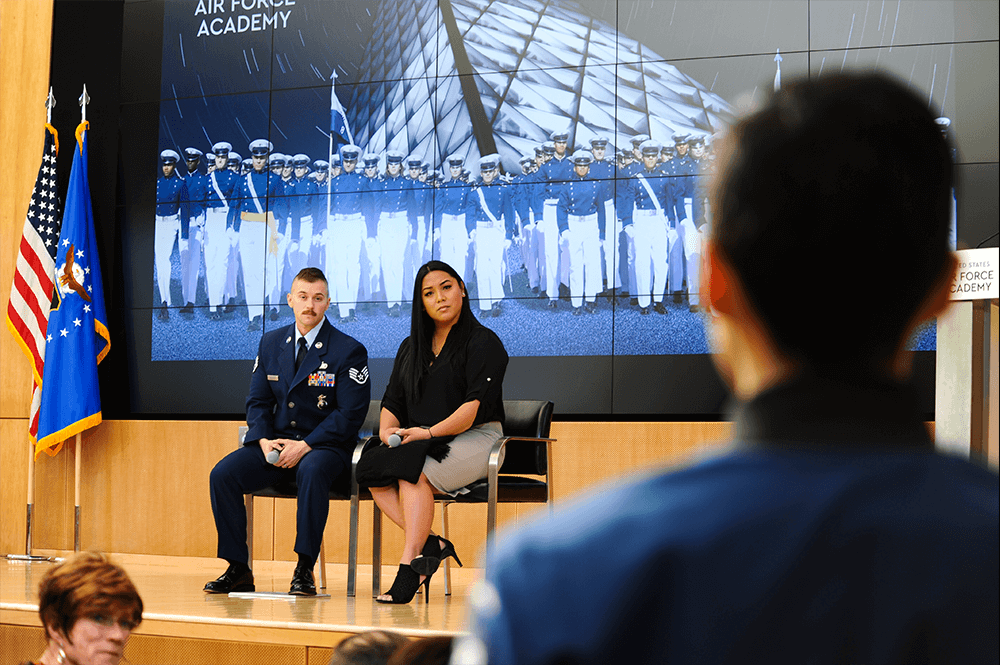

Staff Sgt. Logan Ireland and his wife, Laila, speak to an audience in Polaris Hall about transgender issues during the National Character and Leadership Symposium hosted by the U.S. Air Force Academy, Feb. 22-23, 2018. (U.S. Air Force photo/Tech. Sgt. Julius Delos Reyes)

By Master Sgt. Jasmine Reif, Feb. 26, 2018

U.S. AIR FORCE ACADEMY, Colo. — A military husband and wife shared their experiences as a transgender couple with cadets and faculty Feb. 22-23 during the National Character and Leadership Symposium hosted by the Air Force Academy.

Staff Sgt. Logan Ireland is a security forces Airman at Peterson Air Force Base and his wife, Laila, was a soldier for 12 years before her medical retirement from the Army.

The Logan’s were featured in a 2015 New York Times documentary, “Transgender, at War and in Love.”

They spoke about this documentary and their life during a Q and A session with their audience at NCLS. Here are excerpts from that session. The Logan’s responses were edited for length and clarity but the complete Q&A session can be found on the Academy YouTube channel at USAFAOfficial.

Tell us a little bit about yourselves.

Logan: When I joined the Air Force in 2010, I joined for the reasons many of you joined. I was a full-time college student paying for college out of my own pocket. My education got a little pricey, so I ended up enlisting in the Air Force. I’ve loved it ever since and have been making a career out of it. Since I joined, I’ve been to three duty stations, been deployed twice and been on countless [deployments], but it wouldn’t have been that way if I didn’t have leadership backing me up every step of the way through my transition. Having that leadership and steering me was pivotal to the success of my career.

Laila: I am from Honolulu, Hawaii, and am the great spouse of this fine man. In my career, I deployed twice to Iraq and now my work includes advocacy and going places to talk to people about diversity inclusion in school spaces and work places, but mostly with a specific emphasis on transgender in the military.

How has your life changed since [“Transgender, at War and in Love”] was released?

Logan: When we put out this film, we did it for a very selfless reason. It was not about us. There were so many people who came before us who were discharged out of the military and were unable to live an authentic life. Every day, I put on my uniform and I think about those who came before me. All of you might be a commander over me one day in a deployed setting or home station, so I would hope I could influence you guys and your leadership for people who may come after us.

In the military, we’ve had people from certain genders and ethnicities who have overcome challenges. For example, African-Americans and women being allowed to fly. Do you think that change will come for Trans-genders?

Logan: It really takes leadership from the top to bring that dignity and respect down to all the troops – so that’s really the foot stomp.

When I’m on the news or on social media, I hear U.S. representatives, service members or my peers make the argument that the military is not a social experiment and the military should not involve itself in the transgender issues. How do you respond to that?

Laila: I believe we are the greatest military in the world. I am biased because I was in the Army for 12 years. I believe the American military was built on diversity and every time we include a different type of person or group, we advance ourselves forward. Each team I was a part of, every person came from a different place, background and culture. Because of that, that team was the best one I’ve ever worked with. So, if you want to call the military a social experiment go for it, because each and every one of you is different, but the one thing that we do share in common is the mission.

One of my youngest brothers is transgender and explaining that to some people can be difficult. What are some of the best ways to start those conversations and get people to open their hearts and minds to understanding something that they’ve never heard of or experienced before?

Laila: When I first came out in 2004 to my family I identified as a gay man, and coming from a Pacific Islander, Hispanic, military, Catholic family — three strikes and you’re out — I was doomed from the beginning. When I came out as transgender to my family, the time it took for them to come around was significantly less because I had to step back and realize there was something different about me coming out as Trans. I needed to look at the bigger picture. It wasn’t just about me, it was about everyone who I also affected, so I needed to be patient while learning with them. So trying to educate other folks during this journey and about the transition program has been difficult. You can talk until you’re blue in the face, but you can only lead the horse to the water, you can’t make [it] drink. So at some point, you can say we can agree to disagree and I respect your opinion and that’s it, but your responsibility is to continue to advocate for your brother or your sibling, and continue to love them unconditionally and be there for them when they need you.

Some people are hesitant or unsure about changes in the military. We’ve heard a lot about what to do as leaders, but what do we do to inspire a culture of inclusion among our peers?

Logan: I would look back in history with the inclusion of African-Americans and women, the repeal of Don’t, ask, Don’t tell. Every decade, we are progressing and every decade we get stronger and stronger. This is your military but also my military, and we all raised our right hand the same and we all put on the uniform the same.

How has the world changed after transitioning?

Laila: In this transition, Logan and I can say we’ve walked a mile in both shoes, boots and heels. Prior to my transition, trying to be a masculine male figure in society, I would go to hardware stores and ask questions and need tools and they would answer me. Now we go to those stores and I would ask the question, but the clerk would not answer me — they would directly answer Logan. So I’ve seen a shift in privilege because I guess men who work in hardware stores think women don’t know anything. But Logan doesn’t know anything about hammers and nails.

Logan: I can attest to that. I don’t know anything about tools. I don’t have a mechanical bone in my body, but those are the typical stereotypes for males and females.

Laila: It has been a change in culture because I get to see how I have become second and I think I understand misogyny more. With the change in culture, we need to recognize the differences and we need to have those conversations about how we can be more respectful toward each other and not just judge someone because they’re female or male.

Could you share the most negative thing that has happened to you, how it affected you, and how you managed to persevere … As well as the most positive reaction you’ve received from a commander and how it affected you?

Logan: I can talk about the positive leadership because that’s what I’ve had in my career. The first thing I did was try and facilitate the open line of communication, keeping in mind respect and the chain of command. I knew I was a new topic. I would ask my commander or whoever was over me (and say) ‘I was born female, it has female on my records, and I look male. Where would you like me to room and where would you like me to use the restroom and how would you like me to conduct training? I don’t want to disrupt morale or readiness. I left it up to them and I think that showed them the respect they needed and deserved with how to help guide me in my career. Now that my gender marker has changed and I’m seen as male every day, we still have that open line of communication.

Laila: The [documentary] showed the contrast in our experiences. My leadership was not so nice. Up until my last tour, my file was remarkable and then I had a change in leadership and they didn’t make it a very pleasant time for me. Leading up to my medical retirement, my therapist and my doctor looked at everything and said you can either stay in and fight and essentially lose this battle, or you can take a medical retirement and get benefits from all the years that you’ve served in the military. At the time, I had to make a really tough decision because I liked putting on my uniform and I loved being in the military. I had pride in being a soldier and now I have pride in being a veteran. We had just started our relationship and so I had to weigh my options, and I had to look at it like he can fight for it from the inside and I can fight for it from the outside. It just goes to show that because of my leadership‘s personal biases, it was a really tough time even though I was being transparent and even though I was trying to do everything the right way.

Would you share how you met?

Laila: We met online through a Trans military support group. In 2012 we talked online. In 2014 we met formally at a conference in Houston. In March 2014, we started dating and in June 2014 we got engaged. We got married in May 2016 and we’re crossing our fingers that we get to adopt our first child at the end of this year.

What advice would you give to someone who doesn’t have a positive supportive commander?

Logan: The best advice I could give is to keep marching forward. Your voice needs to be heard and it will be heard. Don’t give up. With each new decade we grow as a stronger military. Use your chain of command, maybe go to a different peer or maybe ‘up-channel’ [the issue] depending on the situation. But make sure your voice is heard, because diversity really is the key to how awesome our military is. We are a melting pot of diversity in the military for a reason, so let’s not silence anybody with their ideas or their creativity or inspirations.

Laila: Be willing to be open and patient. Willing to learn about something you don’t understand. It’s easy to label something that is different from what we believe and different from what we are, but being open to learning about something you don’t know about is key.